You tore your ACL, now what? There is a common misconception that if you tear your anterior cruciate ligament, you have to get it fixed right?! Maybe, maybe not. Over the last decade we have seen this idea come under more scrutiny and it is becoming harder and harder to justify surgery for everyone that suffers an ACL injury.

First, a brief recap on my own personal ACL story (-stories). I tore my left ACL jumping out of the back of a truck in college (no beer was spilled in this event). MRI revealed a full disruption of my ACL and I was referred to an orthopedic surgeon shortly thereafter where I underwent ACL reconstruction (ACLR) using a patellar tendon graft. Being the typical college-aged male, I was not very compliant with my PT and went back to playing sports too soon without any formal testing to assess my readiness. My knee had several hyperextension moments and never felt quite “right” but I was young, active and strong and outside of a few scenarios it never really bothered me. Fast forward a few years and now I am in graduate school pursuing my doctorate in physical therapy (sidenote: I was a terrible patient but this injury introduced me to an industry that became my calling so...WIN!) and I tore my opposite ACL in an indoor soccer game. This time around, mostly because of my age and subjective report of my other knee not being so great, my surgeon and I elected to use a cadaver graft (allograft). I knew more, was more passionate about rehab, and was far more compliant. Alas, the physical therapy I received was underwhelming and again, never completed any formal return-to-sport testing. Neither knee was ever quite whole again and when tested a decade later, I demonstrated about 17mm of laxity on the right and 12-13mm on the left (average for men is about 4-8 mm, Wroble et al. 1990). I am “ACL deficient” in both knees. So I should get these fixed (again), right? Not really. I have no instability in my daily life, I can participate in all meaningful activities with no limitations, and the things I cannot do well (reactive pivoting-type sports) are not important to me. In fact, I compete at the national level in powerlifting, recently squatting 501lbs and set a national record for my age in the squat. I ran the Reno-Tahoe Odyssey twice, I wake-surf, snowboard, and can play with my kids. Not too shabby! I am both a statistic for ACL re-injury as well as for the potential to be highly active without surgical reconstruction. I am not an outlier or an exception.

I share this because I can appreciate both sides of the argument (surgery vs non-surgery). Many patients (98%) believe ACL surgery will “fix” their knee and 91% believe they will return to their pre-injury level but only 55-65% actually return to their prior level of athletic function (Feucht et al., 2016, Ardern et al., 2014). Seems to be quite the disconnect between patients’ beliefs and reality. What about arthritis and future meniscus damage? Many people are told to get surgery whether they have any limitations or not to prevent these joint changes from happening. Unfortunately, the literature does not seem to support this idea. A recent study by Ekas et al. showed the risk of secondary meniscus injury to be between 0% and 52% (that’s a big window….aka suggests “very low certainty”). Their findings suggest that there is little to no evidence that surgery will prevent new meniscal injury and conversely, that those that decide to pursue non-surgical intervention will not suffer meniscal injury down the road. Insert shrug emoji here.

Image source: Wang et al. 2020

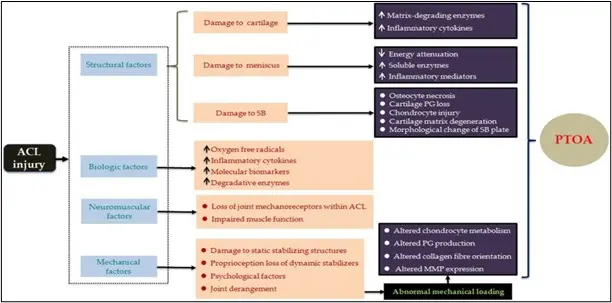

What about arthritis? Zadros and Pappas report in their commentary published in 2019 that 40% of patients who suffer an ACL injury will develop osteoarthritis on imaging whether they get surgery or not. Perhaps the ACL injury itself is the catalyst for arthritis (commonly referred to as Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis or PTOA)? Wang et al. state “convincing evidence is still lacking for the superiority of ACL-R to conservative management in term of the incidence of PTOA” This begs an entirely different blog post on osteoarthritis itself (hint: it doesn’t correlate well with pain, dysfunction or quality of life...check out some of Greg Lehman’s fantastic work here on this topic 1,2,3). Zadras & Pappas go on to suggest that perhaps conservative management of ACL injuries should be the “first-line treatment” and that decision making for getting ACL surgery should be “as-needed”. So a general recommendation of getting surgery only if you need it?? Fascinating.

So what are the takeaways? First, getting ACL reconstruction is no guarantee that you will return to your prior level of function. Second, getting ACL reconstruction does not guarantee that you will not retear your ACL in the future. Third, the argument that early ACL reconstruction will prevent future arthritis or meniscal injury is not well-supported in the literature. Fourth and finally, you CAN return to a healthy, athletic lifestyle without an ACL. This doesn’t mean surgery isn’t indicated for some people OR that your days of being an athlete are done and gone after ACL injury, surgery or not.

So who should get ACL reconstruction surgery?? Candidates for surgery might be those individuals with significant mechanical instability (giving out, buckling) that have not succeeded with conservative management > 3 months or have concomitant injuries in the knee, those who wish to go back to pivoting and cutting-type sports (although evidence suggests this is also possible for many who do not get surgery as well! Grindem et al., 2014) , or those under the age of 25. We typically recommend for patients, depending on a variety of factors, to focus on getting stronger, finding a qualified PT and managing their workload first and should they still find they cannot participate in meaningful activity, then ACL surgery is still an option! Check out our favorite strengthening exercises for those that wish to avoid surgery and if you found this blog helpful or would like to speak to a PT regarding your injury, reach out to us here.

References:

Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five percent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and metaanalysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(21):1543–52.

Feucht MJ, Cotic M, Saier T, Minzlaf P, Plath JE, Imhof AB, et al. Patient expectations of primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(1):201–7.

Filbay SR, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2019;33(1):33-47.

Grindem H., Eitzen I., Engebretsen L., Snyder-Mackler L., Risberg M.A. Nonsurgical or surgical treatment of ACL injuries: knee function, sports participation, and knee reinjury: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(15):1233–1241.

Wang LJ, Zeng N, Yan ZP, Li JT, Ni GX. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis following ACL injury. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020 Mar 24;22(1):57.

Wroble R, Van Ginkel L, Grood E, Noyes F, Shaffer B. Repeatability of the KT-1000 arthrometer in a normal population. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(4):396–9.

Zadro, J.R., Pappas, E. Time for a Different Approach to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Educate and Create Realistic Expectations. Sports Med 209;(49):357–363